We investigate how European Union Funds were used for projects to develop human resources in Bulgaria, where 1.2 billion Euro of EU money was available to spend between 2007 and 2013

A winner of a quarter of a million Euro project was run by the mother of an MP and regional leader on the committee which oversaw the grantor of the funds, the Ministry of Labor

Inspectors of EU-financed human resources programs still do not have the capacity to guarantee whether training is undertaken by legitimate instructors or even happens at all

Despite massive suspicions of fraudulent activity, only 215,000 Euro has been held back as refused payments or unpaid grants on projects, a mere 0.25 per cent of the finances granted

In Bulgaria, where hundreds of millions of Euro have been spent on roads, water infrastructure and parks with the help of EU financing, a couple of 100,000s in cash from the member states was a drop in the ocean.

But this amount caught the eye of the authorities in a high-profile scandal involving a senior politician.

The money was part of a ‘voucher’ scheme under the 2.4 billion Bulgarian BGN (BGN) (1.2 bln Euro) program ‘Development of Human Resources’ (OPDHR) which used EU money to train the jobless and unskilled between 2007 and 2013.

This was financed by the European Social Fund and the projects were managed by the Bulgarian Ministry of Labor.

In the scheme, the Bulgarian Agency for Employment gives “vouchers” to citizens who wanted to learn new skills, which they use in pre-approved centers, such as an office for teaching IT or languages, or a kitchen for cookery.

These are the Centers for Professional Training or CPTs, which receive EU cash in exchange for vouchers from the trainees. The value of each voucher can range from 600 to 1,800 BGN (300 to 900 Euro).

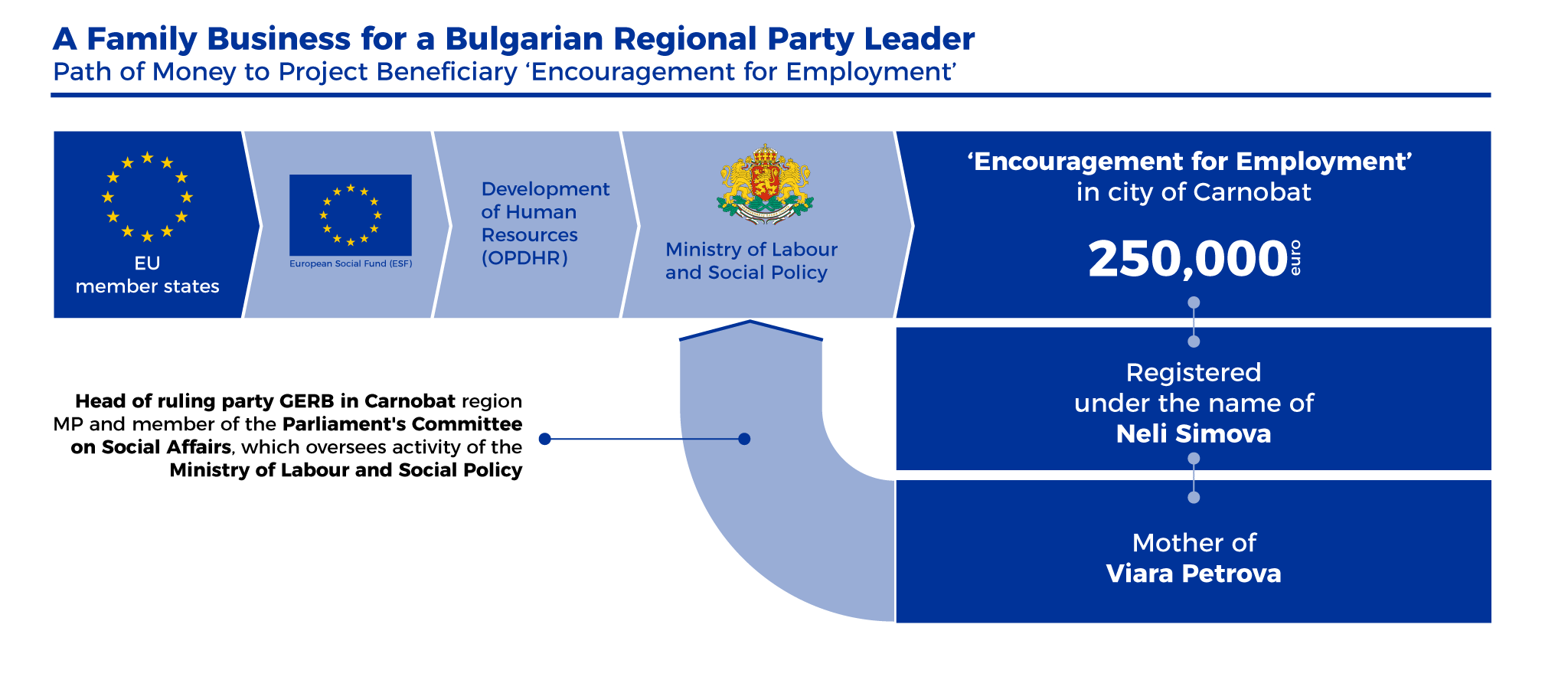

But in 2012, the Socialist opposition to the leading Conservative party (GERB) flagged a problem. One CPT called ‘Encouragement for Employment’ in Carnobat, east Bulgaria, registered under the name of Neli Simova, had won over 500,000 BGN (around 250,000 Euro) in European Funds.

Simova is the mother of Viara Petrova, who was an MP for GERB at the time, as well as the leader of the ruling party in the Carnobat region. Also, she was a member of the Parliament's Committee on Social Affairs, which oversees the activity of the Ministry of Labor and Social Policy, the grantor of these EU funds.

‘Encouragement for Employment’ was registered in the 1990s, but in April 2012 the center sought to expand, by boosting the number of specialist areas in which it was qualified to train. A center can add as many training areas as it wants for a minor fee of around 1,000 BGN (500 euro) per skill. All it has to do is present a list of teachers who are under contract, along with their training bases. Whether these courses were of any quality - or even happened - was hard to determine, as monitoring of these projects was rare.

Several months later ‘Encouragement for Employment’ won almost half a million BGN (250,000 Euro) in vouchers. One of the schemes was especially problematic, as the vouchers were used by staff in one of the busiest seaside hotels, Elenite, near the tourist hub of Sunny Beach, during the summer high-season.

It was obvious that no hotel would allow its employees time off for a whole-day training during the busiest time of the year. Something was wrong, so the state-run Agency for Employment, which oversees the voucher scheme, checked up on the activities of ‘Encouragement for Employment'.

Scandal-plagued Politician “hit” by Prosecutors

After the news broke, the parliamentary Commission on Corruption demanded an interview with the deputy, Viara Petrova. The Agency for Employment carried out 148 checks on ‘Encouragement for Employment’ over two months, which was an unprecedented level of scrutiny. Those checks, the Agency argued, found a range of irregularities, and the EU cash-flow was turned off. The center did not receive the 190,000 BGN (95,000 Euro) it was owed for the voucher scheme, claimed the Agency at the time. The head of the local Labor Bureau was fired with unclear motives. Later, the head of the Agency for Employment, Camelia Lozanova, was also dismissed, and Petrova announced she would resign as an MP.

But the Commission on Corruption, controlled by GERB, found no reasons for concern regarding Petrova and handed her over to the Commission for Conflicts of Interest.

One of this Commission’s opposition party members, Maya Manolova, said she felt “uncomfortable“ questioning Petrova, as her answers didn't make much sense and she kept on claiming there was no connection between her and the CPT in question, despite the fact it was owned by her mother.

The Commission took several months to reach a decision. It later stated that the deputy had not been in breach of the rules.

However, according to the Parliament Registry, Petrova did not resign, and the only reason for her failure to finish her mandate was the fall of the government and new elections in 2013.

Several months after the new elections, the ex-chief of the Commission for Conflicts of Interest, Filip Zlatanov, was charged with violating the duties of his position, because his diaries showed initials next to orders on whom his Commission should “hit“ and whom to “spare”. Despite his status as an independent prosecutor, he had placed next to Viara Petrova’s name a mark “to hit“.

Petrova now claims she was the victim of a smear campaign and maintains there was nothing illegal or wrong in how training was undertaken or how the money was earned by the center.

“The CPT was operational long before I entered politics,” claims the ex-deputy. Now she is no longer in GERB and, when we asked her if she felt like “a scapegoat”, she refused to answer.

We tried to reach the former head of the Agency for Employment Camelia Lozanova, who was laid off after the case with Petrova, but she declined to comment.

Where did the money go?

We compiled the numbers from all the records of the voucher schemes won by the training center of Petrova’s mother.

These show that the money withheld by the Agency for Employment from the politically-linked CPT was not the full 190,000 BGN that was initially claimed by the Agency.

The database reveals that only 39,000 BGN (24,500 Euro) was unpaid, which is just under one fifth of the total.

So despite the scandal, the CPT received most of its money. Now Petrova says that even these withheld payments from the Agency to ‘Encouragement for Employment’ were wrongfully stopped, and should have been paid to her mother’s training center.

Also, during the controversies in 2013, ‘Encouragement for Employment’ won other contracts with EU funds, including 116,700 BGN (58,000 Euro) for vouchers. Several months after the scandal, the center also won a strange grant from the same program. The contract was for 180,000 BGN (90,000 Euro) to create an e-platform for a school in Aitos, a municipality near Carnobat, where Petrova was a deputy.

Because ‘Encouragement for Employment’ did not have the capacity to deliver the program, it acted as an intermediary. The center tendered the creation of the platform to a little-known Sofia company with no website at the time, called ‘CallCen’ (today the site is still not operational). There is no obvious reason why a CPT would win a grant for IT work and tender it out to another company.

Today, the companies registry shows that ‘Encouragement for Employment’ was delisted in 2018, so it seems its current lack of political connections in high places has not been compensated by the purely professional training it provides. However, there is one curious detail in the company registry. Under ‘Person to contact’ is a familiar individual. Despite earlier claiming there was absolutely no connection between her and this firm, in black and white, appears the name of Viara Petrova.

When we confront Petrova about her name appearing on the CPT, she claims she entered the training center “two of three years” after she left politics.

Check-ups on training were at dismal rate

The State Agency for Professional Training and Education (NAPOO) is not easy to find. Its office is hidden far from the center of Sofia, in a building behind a pub, between the blocks of Sofia University, on the fifth floor. Outside is a new glass elevator, but inside the only innovation seems to be an aluminum door on the agency floor.

Due to the activities of this office, 174 million BGN [89 million Euro] has been granted to beneficiaries of EU funds between 2007 and 2015. The small state department, under the wing of the Ministry of Education, has two functions: to develop standards on vocational training and education, and to license centers who want to undertake this training. Therefore every one of over 1,000 CPTs in the country has passed through the agency on its way to accessing dozens of millions in EU money.

NAPOO’s Final Report of 2015 states that more than 184,000 people have been trained in this multi-million bonanza. This means that, between 2010 to 2015, an average of 82 people have attended courses every single day. How can such a flow of money and people be verified?

Emiliana Dimitrova, the director of NAPOO, points out the shortcomings of the system. “I have 20 people and there are over 1,040 centers,“ she says.

To obtain a license, candidates submit contracts for a list of qualified teachers, as well as a physical base, such as office for IT teaching, or a kitchen for cookery.

Checks are made by the Agency for Employment, which manages the voucher programs. “But they have no experts to evaluate the bases and teachers, so they invite us, and we plan 130 inspections a year,“ explains Dimitrova.“Apart from that, we cannot guarantee whether the training is done by the legitimate instructors, in the legitimate places or if the training is done at all.“

Is it possible that someone who receives vouchers does not undertake any training?

“That question is for the police,“ she says.

Near-Zero Fraud Cases

We also spoke to a source from the Agency for Employment who participated in monitoring the EU-funded courses between 2007-2013.

“We did not have enough capacity to check up on the projects,“ he says. “For example, if there was training in Shumen [a city in the central east], we went up for one day, on expenses, and did not see anyone in the classroom. We reported this, but the trainees were entitled to be absent from the courses for up to 20 per cent of the time. We could not go back day after day to Shumen.”

According to him, cases similar to the one involving Viara Petrova are not isolated. He gives another example. The voucher scheme allowed company managers to enroll their employees for training. Staff members in some companies signed a piece of paper from their manager, but did not know what this was for, and did not know they were supposed to receive training. The training did not take place, and the CPT and the company managers divided the EU cash for the vouchers.

The existence of such a scheme - which is theft of EU money - is confirmed by the supervisor of the whole program, Deputy Minister of Labor and Social Welfare, Zornitsa Roussinova.

Due to such fraud attempts, the system has now changed, she argues. “When there is money involved,” adds Roussinova, “there will always be irregularities.“

Whether the control mechanism in place now works is controversial. The Agency for Employment website shows that only 430,000 BGN (215,000 Euro) has been withheld as “refused payment“ or “unpaid“.

If we use only this breakdown against the total amount for voucher schemes, which were worth around 87 million Euro, the unpaid and the rejected money is only 0.25 per cent.

A 2015 report by the European Court of Auditors states that the estimated level of error in EU financing of projects, which measures the level of irregularity, is 3.8 per cent. In Bulgaria this rate is usually between one and 1.5 per cent.

Despite the widespread suspicions of fraud, these schemes have one of the highest levels of honesty and propriety in the EU.

EU Human Resources Cash: Used to Pay Salaries

The human resources program was used partially for a different purpose than its original plan, because it was implemented in a time of a dire financial crisis (between 2009 and 2013), and many companies turned to OPDHR as a buffer to supplement salaries to their employees, rather than as a tool to train the workforce.

Also as part of the program, 44 municipalities were allowed to set up enterprises to fight unemployment and employ people from minorities. Many of those municipalities were small. What this meant is that the Governing party, in control of funds disbursement, used this as a subsidy to help a certain demographic - mainly low income - with jobs.

These people tended to vote in groups and often under instruction from party bosses, and a concern was that such jobs were used to win electoral support. A former Minister of Labor and Social Policy, Hasan Ademov, speaking in general in 2014 about state programs that use subsidies for employment, called them “an instrument for political influence“.

Some of the institutions tasked with managing parts of the program could not exert control over such a large scheme. Take for example the Agency for Employment. This is a mammoth structure with nine directorates in Sofia and over 250 local Labor Bureaus employing over 2,400 people. It has coordinated huge amounts of EU financing: up to 640 million BGN (327 million Euro approx.) from 2013 to 2016 through OPDHR. Yet it does not have the power to verify what happens to this money, and is a poor administrator, according to people we spoke to within the system, and companies who have dealt with the agency.

In one visible failure, in March 2016, the Agency opened an electronic tender system for EU grants on Friday afternoon and closed it on Monday, leaving it open for a total of only two hours. When the winners were published, it turned out only 157 from over 3,500 companies accessed the scheme, all of whom had applied in the first 19 minutes. Some of the winning businesses were created a few days before the procedure, while others had been inactive for years, which caused much suspicion about the transparency of the process.

Because of the public outcry, the ministry ordered the Agency to restart the procedure.

Hairdressing Salon: Training in Welding

To detect fraud, trainees can “whistleblow“ on problems in the courses where they learn.

This year Capital newspaper received information about a poorly-executed voucher scheme for interior design as part of the ‘“I Can Do“ and “I Can Do More“’ project. This was an EU-financed project under OPDHR, which citizens had the freedom to choose their own courses.

Because of the deficiencies in the training, an unsuitable base and poor organization, the training company ‘Informa’ was punished by the Bureau of Labor, and payments on these vouchers were suspended.

Such information, however, can usually only be obtained if learners have a personal motivation to participate in training. This happened in “I Can Do“ and “I Can Do More“, since these were employee-driven programs with tens of thousands of real participants.

In schemes where the employer or the municipality enroll a large number of people in courses, the trainees can hardly be expected to take the initiative to criticise the teachers, even if the training is poor or non-existent, without angering their bosses.

Therefore, we compared the rankings of the 20 most profitable training centers in all schemes available, and the 20 most profitable centers that are part of schemes where trainees are enrolled by their employers, to see if there is a difference.

Some of the names emerge in both rankings, but others appear only in the second grouping.

Take a chain of hairdressing salons from the northwestern city of Vratsa called ‘Mexico-PE-Peter Yordanov’. The CPT that is connected to ‘Mexico’ is registered for training in almost 110 skills. They range from welding and finance to tailoring. However, this company only appears in the ranking of the schemes where trainees were enrolled by their employers.

It has made around 630,000 BGN (315,000 Euro) in vouchers, of which just under 100,000 (50,000 Euro) are from “I Can Do“ and “I Can Do More“’, where trainees have the freedom to choose. Predominantly, the picked courses in the core specialty of the firm - hairdressing and cosmetics. So when deciding what to do with their vouchers, people mostly didn’t opt for ‘Mexico-PE’ for any of the other 108 specialties in which it claims to offer courses.

Yet most of the other 530,000 BGN (265,000 Euro) in vouchers and procurement the training center received had nothing to do with hairdressing and cosmetics - and instead came from the dozens of different listed skills.

A representative of the ‘Mexico’ CPT said that “fashion trends in business-cycles determine what people want to study for“.

Eventually the salon chain grew tired of the voucher schemes during the 2014 to 2020 period, where individuals choose their trainers, and the company is no longer interested in working in this field. Instead it offers private training outside of those sponsored by the EU.

“Problems Solved"

All of the state parties in control of the scheme claim that the irregularities during the first period of the EU-financed ‘Development of Human Resources’ 2007-2013 have been corrected for the second round.

For example, there were fraud attempts in the distant learning schemes, according to Deputy Minister Zornitsa Roussinova, which is why these programs are now forbidden. During the second round of 2014-2020, there has been no financing for enterprises run by municipalities. Employers can no longer sign up their employees for training without their knowledge, as voucher schemes require not only the personal agreement of the worker, but they must co-finance 15 per cent of courses with their own money.

“There were also companies winning grants in joint-ventures with CPTs,“ says Roussinova. “This has been forbidden if the CPT is not completely owned by the company. In all the other cases they have to announce a tender.“

Meanwhile the State Agency for Professional Training and Education (NAPOO) has realised that problems were abundant in the first period, so has increased its number of check-ups from a handful before 2014 to 130 per year today.

Part of a project financed by Journalism Fund

Opening picture: An anti-government protest in Sofia on July 24, 2013, Sofia, copyright: Dimitar Dilkoff, Guliver/AFP

Infographic by Studio Interrobang