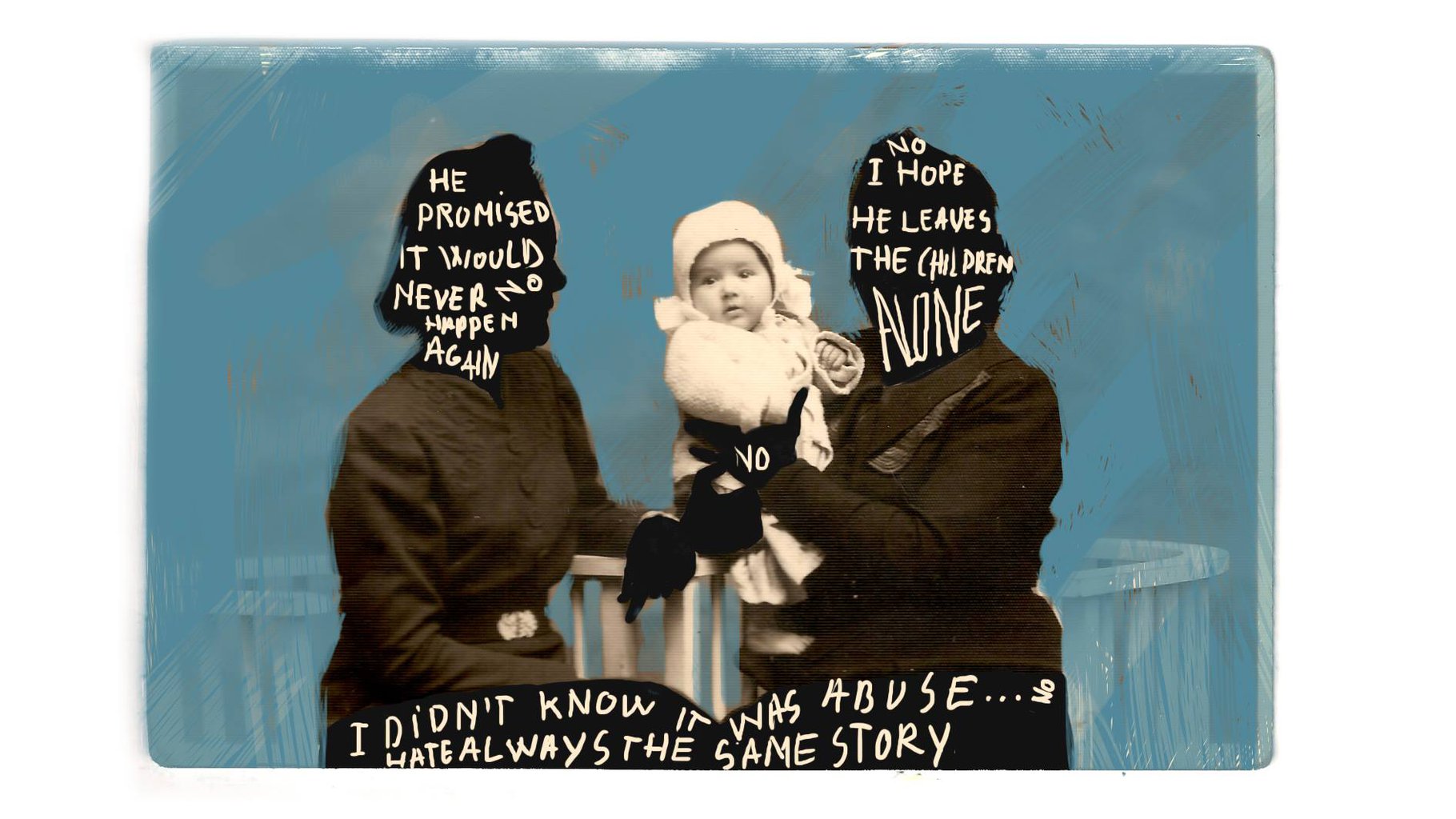

“Stop loving Mummy.”

These words came from Petre - a 33 year-old officer from the Ministry of Interior to his two-year old son.

He spoke in front of his wife Ana, a manager in the financial services sector in the apartment they were both living in. A place which she had bought with her decent salary.

“Your Mummy is crazy,” he added.

Ana tells me this in an exasperated tone, opening up about her past, listing attack after attack of a three-year ordeal of physical and psychological torture from her husband.

During this time, he beat her body, including kicks and slaps, and threw her against the wall.

Although he never hit their baby son - the boy, now only learning how to walk, was watching the episodes.

Once the baby tried to kick his mother with a menacing drive - in imitation, she believes, of his father.

Now Ana has escaped from this situation, but will not tell me where she and the child live, because she is in fear of her husband - an influential figure in the Ministry which oversees the country’s police.

So we talk in the safe environment of the Directorate General for Social Assistance and Child Protection - in a small crowded office, piled with papers and folders, with two social workers present.

Ana is wearing a white shirt and blazer, trouser-suit, subtle lipstick and shoulder-length hair, well-coiffured - giving her the look of a middle-manager in a large international corporation.

She speaks with clarity and eloquence about brutality suffered at the hands of her husband and her attempts to find justice in a system which is not always receptive to the complaints of battered women.

Ana was seven months pregnant, when he slapped her face for the first time.

Soon this became routine.

He beat her after she gave birth, including moments when she was holding the new-born in her arms.

“He kicked me in the legs and some veins in my legs burst - the marks still remain,” she says.

Ana believes this is because she fell out of favor with her mother-in-law, Sara.

It started with a typical domestic incident.

Sara asked for the keys to Ana’s apartment, so that she could come and go anytime. Ana refused.

When her mother-in-law found out that Ana was pregnant, she wanted her to have an abortion. She “only wanted her son” for herself.

The mother-in-law was never present when Ana’s husband would hit her, but Ana did tell her about the beatings.

The mother-in-law replied:

“Petre can continue hitting you because if he beat you and you came back, it means he didn’t beat you enough.”

During Ana’s pregnancy, her husband started meeting other women. Part of his justification for this was that due to a complicated pregnancy, Ana could not have sex.

He would go out, take other women to his mother’s apartment, come back home and slap his wife.

The mother-in-law threatened to kill both Ana and the boy.

Petre took the child away from her. At that point, Ana filed a complaint with the police. Her husband’s boss - also a woman - then called her, telling her that if she gave the police the results she received from the forensics – proof of the abuses she had suffered – she would not see her child for the next three weeks.

She also recommended that Ana should see a psychiatrist.

But Ana believes that if she had sought therapy, the state could have stripped her of her rights as a parent.

Eventually he brought the child back home. But Petre was afraid the incident could affect his status at work, so planned to create the illusion that she was not mentally fit.

This started with him recording her conversations. In one instance, she was chopping vegetables in the kitchen, while he was pointing the microphone towards her, stating for the record: “Why are you pointing that knife at me?”

He told her he would send her to “Spitalul 9” - the notorious Obregia Mental Hospital in south Bucharest.

One morning her husband drove her to work, parked outside her office and they had an argument, which ended in him squeezing her arms with such intensity that they bruised.

At work, she sat down opposite her computer and looked at the swelling and marks across her hands and arms.

She thought at that point - if I go back home and stay with him, I will go insane.

Eventually Ana took her child and, at her lawyer’s advice, found refuge in a women’s shelter.

Ana has gathered evidence against him, but Petre told her that due to his high position, nothing would happen to him.

At first - this seemed to be the case.

After leaving her house Ana went to the police to file a complaint against her husband. The police officers refused to register her statement.

Ana was also followed around town by two of her husband’s work colleagues.

Since then she has been in search of a platform that could help her with justice - including a military court and another regular court.

Immediately after leaving home for the center for abused women, Ana asked for a restraining order against her husband, the legal instrument offered to abuse victims (known in the UK as an injunction) - which after a few weeks she won.

Now her husband is not allowed to see the child.

'One woman beaten to death every three days'

In the EU around one in four women have experienced or have witnessed at least once a situation of domestic violence. In Romania, the exact number is disputed.

Experts believe this is because the majority of cases go unreported.

The Association for the Promotion of the Woman in Romania (APFR) believes one in three families experience domestic violence.

Meanwhile official figures from 2010 reveal one woman is beaten to death every three days in Romania.

But the view in Romania is that domestic violence is a blight that affects the poor, the drunk and the Roma minority.

“In the media there was not enough documentation of cases [of middle-class abuse],” says Simona Burduja, a psychotherapist at the Sensiblu foundation, which runs a shelter to help victims of domestic violence in Bucharest.

“A popular idea is that persons who are in an abusive relationship, or who even stand years on end of abuse have a low social and low income status.”

TV broadcasts a daily feed of red-faced husbands naked from the waste up slapping about their wives and kids between shots of plum brandy in a media farce meant to entertain the mass and confirm their prejudices of domestic violence as a sport of the poor.

“Violence does not appear only when alcohol is involved and in poverty-stricken families,” says Valentina Rujoiu, professor at the Faculty of Sociology and Social Assistance in the University of Bucharest. “We should give up this myth.”

While researching this subject in depth over three months it is clear to me that physical and emotional abuse towards women is a massive problem among the graduate classes.

As I moved deeper into this subject, I found more women opening up to me - including entrepreneurs, managers, doctors and scientists with nowhere to turn to and no one to listen to their shocking history of pain [Read Eleonora’sand Mihaela’s stories].

Women who are aware of domestic violence say nothing because the tradition is still alive that couples should not “wash their family’s dirty clothing in public,” according to Rujoiu.

“Silence prevails, and measures are only taken when the situation becomes extremely bad,” she adds.

Looking into the causes of domestic violence, some experts refer to studies showing that either the abuser or the victim have witnessed some sort of violence or abuse as children. But this is not necessarily a rule.

Mihaela Mangu, director of the Bucharest based Anais Association, which offers free legal counseling to victims, also believes that violent situations are born out of a man’s wish to dominate.

The only difference between the middle and lower classes is the way the violence happens. In lower class households, Mangu says that a way for men to demonstrate power is to forbid their wives from working.

However she believes that many men find it comfortable that their wives bring more money in the house or are the breadwinners.

Valentina Rujoiu also argues that many men in Romania marry for housekeeping because they lack the autonomy to manage on their own.

A problem can emerge when the wife’s job prospects take off, while the man’s are left floundering.

Rujoiu believes that - on many occasions - men feel emasculated and intimidated by their wives’ careers.

As Romania moves into a post-industrial society more dependent on the service economy, where women often succeed faster than their male counterparts, men can project their frustration and disaffection into violence against their spouses.

"You should kill yourself now"

A sunny afternoon in July. I’m sitting at work in front of the computer. My phone calls. An unknown number. I answer. A woman’s voice. She is crying and can barely speak. Eventually I work out what she is asking for.

“Is this a hotline,” she says, “a hotline for abused women?”

I realize a month ago I posted my number as a comment in an online article about domestic violence, for women who were willing to talk to a journalist about their experiences of domestic abuse.

She says she is about to slash her wrists.

I explain to her the situation, state that I have no training and ask if she wants to talk.

As she recounts her experience, she has to take long breaks. Sometimes this is so she can think, and, at others, it is space to cry. We talk for over two hours.

Ioana is 44 and her partner Dan is 47. They live in a large city in Romania. Ioana comes from a well-off family and they both live in the house she inherited from her grandmother.

They started their relationship when she was 17. Six years later she was pregnant.

Ioana cannot reveal her identity, because she says she is an “extremely public person”. Everyone in town knows her and her husband. They are a model family. In 20 years, Ioana has only told two people about her experience.

Dan is a magnum cum laude graduate in agriculture who has worked as a manager for a multinational, while Ioana was an entrepreneur with her own business in event management.

Working 16 hour-days, Dan was in a high pressure job and, in the evening, he would come home to beat and rape his wife.

Ioana has suffered a broken nose, broken ribs and fractured shoulder. Every time she goes to Accident and Emergency, she tells the doctors she has fallen down the stairs.

But now the abuse has crossed a generation. Ioana is beaten by her 22 year-old son - a successful student and popular man about town.

The day before she spoke to me, she told me about an incident in their house, where the family all live.

Everyone cooks their own meals at different times, but Ioana has to clean up after the men.

Her son was in the kitchen and she asked him if she could prepare her own food.

“Are you blind?” he shouted at her. “Can’t you see I want to cook some pasta for myself?”

Ioana told him to speak politely to her.

He threw the food on the table in the floor, the dishes against the wall, the radio and everything he could find within reach around the kitchen.

Fragments of crockery sprayed into Ioana’s face and neck, cutting into her skin.

“You should kill yourself because I hate you, you’re fucking crazy,” he told her, as he pushed her away.

Sometimes he hits her in his father’s presence - but Dan says nothing.

Ioana has been reading on the internet about abused women and believes she is suffering from Stockholm syndrome - where women empathize with their abuser as a coping strategy for dealing with victimization.

“My son is hitting me, my husband is humiliating me, and I remain. It is not normal; it cannot be that I am beaten, reduced to nothing - and I stay at home.”

Before she ends the call Ioana asks if there is a hotline for abused women in Romania.

Throughout my research, I have found none.

“When you want to kill yourself,” she says, “it would be great to have someone to talk to.”

I agree - it’s an unhealthy society where a woman poised to cut open her wrists with a knife make her first cry for help to a journalist.

For another story read, Eight reasons why Romania fails its battered women

Names of victims have been changed.

Thanks to: Ana, Mihaela, Eleonora, Madalina and Ioana for speaking up. To my editor Michael Bird, to Stefan Candea for the opportunity, and to my close ones for being there when I was overwhelmed by the research.